-

Full Genomes

review on 7 January 2016

by Craig Macpherson

At a Glance

Summary

I’m glad I bought my 10x WGS from Full Genomes, and I’m glad I didn’t wait until the price of the 30x came down. Despite having to consider any result from the 10x WGS as a rough estimate, I was excited to discover what was possible today, and I was especially interested to read through the 60,000 known variants I carry!

It’s been a challenging experience trying to work out which WGS files are useful, how to open them, and what tools I should use to interpret them. If the Promethease tool hadn’t been available, I don’t think I’d be able to say I was happy with my purchase. Fortunately, the ability to analyse my WGS for only $10 more really made it worthwhile.

I would highly recommend that anyone who’s enthusiastic about exploring their DNA buy their WGS. Even though your WGS won’t come with a user-friendly analysis, if you’re prepared to see information that you don’t understand when using Promethease-style tools, the information you will understand is definitely worth it.

Full Review

I’ve always wanted a digital copy of my DNA, not just so that I could try out all the free analysis tools out there, but because I’m fascinated by the fact that a piece of code governs how we function and grow. So when I saw that Full Genomes had dropped the price of their ‘Whole Genome Sequence’ (WGS), I jumped at the chance to buy it.

This WGS would only be 10x coverage (coverage is a measure of accuracy) and although 30x coverage is generally regarded as the minimum level of coverage needed for accurate results, it costs over $1,000 more than the 10x costs at $725. Therefore, I decided to buy the lower accuracy WGS to get feel for what I could do with it, and wait until the price of the 30x drops below $500 before buying that one too – this should hopefully be sometime in 2016. With this in mind, I decided to consider any insights gleaned from my 10x WGS as rough estimates that shouldn’t be relied on.

Product Expectations

The Full Genomes site said I’d receive my WGS, that several parts would be analysed, and that other parties would be able to analyse it too. My WGS would be provided in BAM file format – a compressed version of the Sequence Alignment/Map file (SAM) that is produced when your WGS is run – and genetic variant summary reports from SnpEff and VEP would be included. I’d also receive Variant Call Format (VCF) files which are summaries of the genetic variants I carry, and that Full Genomes would carry out a level of Y chromosome analysis too.

Ordering Experience

The Full Genomes site was easy to use and purchasing was straightforward, I had to pay a $50 shipping fee as I was ordering from the UK. Three days after placing my order I received an email to say the sample kit had been shipped, and four days later I received the kit.

The kit contained an invoice for $18 for two spit kits and shipping which was odd, but after contacting Full Genomes, they reassured me that I didn’t have to pay this. The paperwork said I’d receive my full Y chromosome sequence instead of my WGS, but I could tell this was just a minor oversight. In order to send the sample back to Full Genomes, I had to pay another $5 for postage – it was a shame that I didn’t receive confirmation that my sample had been received.

Several weeks after dispatching my sample, I received an email inviting me to set up an online account with Full Genomes where I’d access my results.

The Results

A few weeks later I received an email to say that my results were ready. I logged into my account and was invited to download my 19 GB BAM file and my 5 GB ‘Interpretation Results’. The Interpretation Results contained several files with instructions, and these were split by Sequencing lab analysis files and Full Genomes analysis files.

The Sequencing lab analysis files contained the raw data which were generated when my WGS was run. The files focussed on four types of genetic variant: CNVs, INDELs, SNPs and SVs. Although instructions were included for each type, they were very complex, and as Full Genomes had undertaken a separate analysis to the sequencing lab, I decided to focus on their analysis instead.

The Full Genomes analysis files consisted of Y chromosome files, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) files, and files associated to my WGS.

Results Section: Y chromosome files

In terms of the Y chromosome files, since Full Genomes has historically specialised in paternal ancestry, I knew these would contain information about my paternal haplogroup (the population group that my most recent paternal ancestors are associated too), however, it wasn’t clear how I’d extract this information from the Y chromosome files.

When I followed up with Full Genomes, they sent me instructions for two of the files in the Y chromosome folder: variantCompare and haplogroupCompare. These are reports that can be opened using Excel and that show my high-reliability ‘private variants’. These reports also allowed me to compare my results to other anonymous Full Genomes customers, identify recent mutations, and place my variants on the Y chromosome phylogenetic tree – the Y chromosome phylogenetic tree shows how Y chromosomes have mutated and branched over time.

It should be said that the variantCompare and haplogroupCompare reports contained thousands of rows, and I had no idea how to extract any meaningful information from the data. When I asked Full Genomes, they said the haplogroupCompare report showed my paternal haplogroup was S4744+ (also known as CTS11603), but when I looked in the report myself, this appeared alongside hundreds of other designations in the ‘Named variant status’ column, so I wasn’t really sure why S4744+ was more significant than the others.

As well as telling me that my paternal haplogroup was S4744+, Full Genomes also told me what my equivalent haplogroups were – this is because different organisations use different Y chromosome phylogenetic trees.

In the ‘Composite tree’ https://sites.google.com/site/compositeytree/i I was told my haplogroup appears as: ‘I1a1b4 L300/S241’ and ‘CTS11603/S4744’ and ‘23186819 G->A’

In the ISOGG – International Society of Genetic Genealogy – tree http://www.isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_HapgrpI.html I was told my haplogroup also appears as ‘I1a1b4 L300/S241’

Full Genomes also revealed that my Y chromosome was closely linked to two other customers, one from the Netherlands and one from Finland – this was fascinating! A previous test with Britains DNA revealed that my recent paternal ancestors are from Scandinavia, so it was great to see this partially corroborated.

Interestingly, my previous test with Britains DNA confirmed my paternal haplogroup as S4744+, but put me in this subgroup: I-S142 (Scandinavian). After following up with Full Genomes, I learned that S241 (the paternal haplogroup I’m in according to the Composite and ISOGG trees) is a subgroup of the Britains DNA subgroup: I-S142. It’s clear that establishing your paternal ancestry according to your Y chromosome can be very complicated, and I wished there’d been an easier way to see my haplogroup and subgroups as part of the results!

Other reports in the Y chromosome folder let me analyse my data in different ways: gtype reports showed my results in relation to tens of thousands of known SNPs, yKnot reports showed where my haplogroup fits on the ISOGG Y chromosome phylogenetic tree, and Y-STR reports – these analyse a different type of Y chromosome variant known as a Short Tandem Repeat.

Results Section: mtDNA files

In terms of my mtDNA files, I know that mtDNA can be analysed to reveal the ancestry of your maternal ancestors, and mttype files were included that showed how my mtDNA is unique. The files were easy to open using notepad, and they contained a list of the proteins that make up my mtDNA, and two lists of my mtDNA variants (rCRS and RSRS). Unfortunately, it wasn’t clear how this information was meaningful.

Results Section: WGS files

In terms of my WGS files, I received a zipped snpeff.vep.vcf file (500 MB) which identifies where my genetic variants on all 46 chromosomes differ from the human genome reference sequence GRCh37, a common human genome that geneticists refer to when analysing genetic data. I also received a zipped dbsnp.vcf (4 GB) which reports on over 100 million known genetic variants that I may carry.

There was also a SnpEff summary file – SnpEff is a genetic variant annotation tool – and a VEP summary file – VEP determines the effect of genetic variants on genes and other aspects of your DNA. Both summaries were designed for experts so couldn’t make any sense of them.

Results Section: IGV

Several tools were recommended to me for interpreting my zipped snpeff.vep.vcf and dbsnp.vcf files. The first one was the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) which is a visualization tool for genetic data. I downloaded the software and attempted to open my unzipped snpeff.vep.vcf file which I read I’d be able to compare with the human genome reference sequence. Unfortunately, although the software said my snpeff.vep.vcf had been opened, it didn’t seem to contain any data. Instead of contacting IGV for support or looking for ‘how to’ videos, I figured it was probably a tool for bioinformaticians, and not something I’d be able to use without training.

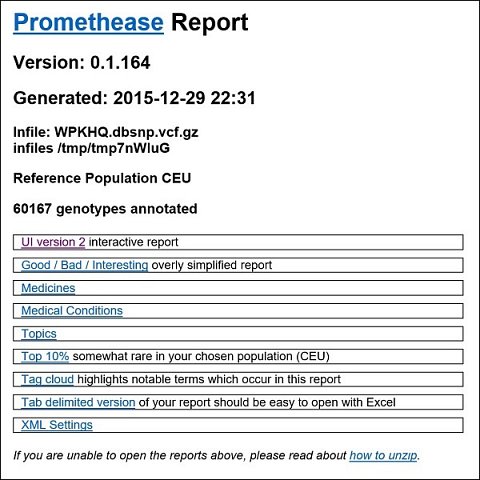

Results Section: Promethease

I was then recommended a browser tool called Promethease, which compared an open source encyclopaedia of genetic variants (SNPedia) with my WGS, specifically my zipped dbsnp.vcf file. It took about 40 minutes to upload this file to Promethease and when it was complete, I was required to pay $10 to see the genetic variants I carried. Upon opening the browser tool, I was told that 60,167 genotypes had been annotated which I believe correspond to 60,167 genetic variants, but it wasn’t clear that this was the case. The opening page of the Promethease report is shown below:

The opening page of the Promethease report.

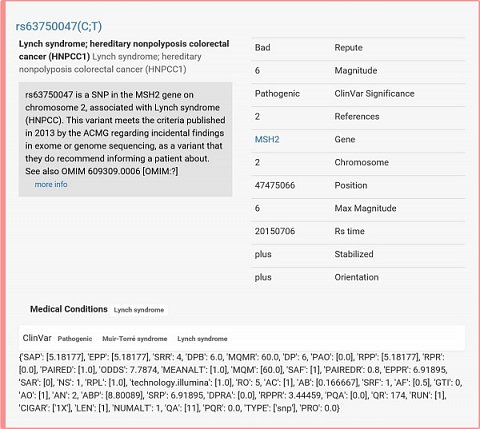

I first accessed the ‘UI version 2 interactive report’ to see a list of the genetic variants I carry (aka mutations or SNPs which mean ‘Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms’) and ‘genosets’ (which are groups of genetic variants). The first genetic variant listed was associated with Lynch syndrome (see below). Possessing it meant that I had an increased likelihood of suffering with this condition, and a link to SNPedia and the scientific papers which backed up the association was provided.

The genetic variation I possess that’s associated to Lynch syndrome.

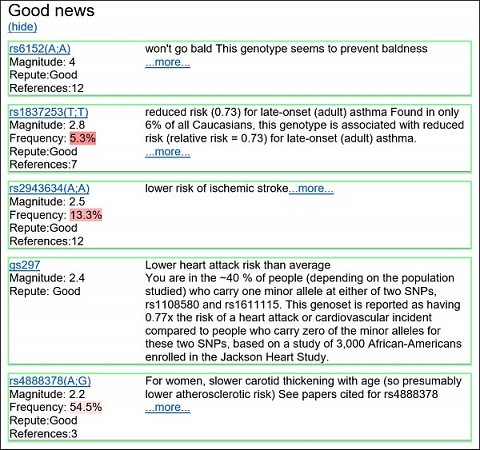

Going back to the opening page, I chose to view the ‘Good / Bad / Interesting overly simplified report’. This listed all the genetic variants that I possess that are understood to be positive, negative or interesting (but not positive or negative). In the ‘Good’ section, I saw dozens of positive variants listed, the top five are shown below:

My top five positive genetic variants.

It was great to see that the top variant indicates I’m less likely to go bald, although another DNA test I’ve taken from International Biosciences revealed that I possess a variant that will make it more likely that I’ll go bald. International Biosciences said I was more likely according to an undisclosed variant of the AR (Androgen Receptor) gene, however, Promethease showed I have five variants that make it less likely (rs6152 on the AR gene, rs2003046 on the C1orf127 gene, rs1160312 on the C19orf26 gene, rs2180439 on chromosome 20p11 and rs2223841 on the X chromosome) and four variants that make it more likely (rs1385699 on the EDAR2 gene, rs8085664 on the SLC14A2 gene, rs6036025 on the C19orf26 gene and rs925391 on the X chromosome).

This is a perfect example of how much more information you get with your WGS. The single variant that International Biosciences use to establish baldness risk doesn’t tell the whole story, there are many more known variants that have an effect, and I’m sure there are others that have yet to be discovered. Interestingly, I’m 34 and do indeed show signs of male pattern baldness, but not to the extent that my father had at my age. The interplay between these nine variants identified via Promethease goes some way to explaining why.

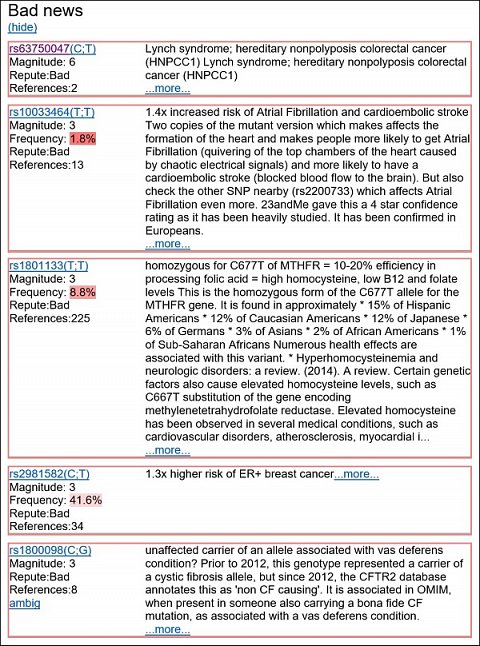

In the ‘Bad’ section, I saw dozens of negative variants listed, the top five are shown below:

My top five negative genetic variants.

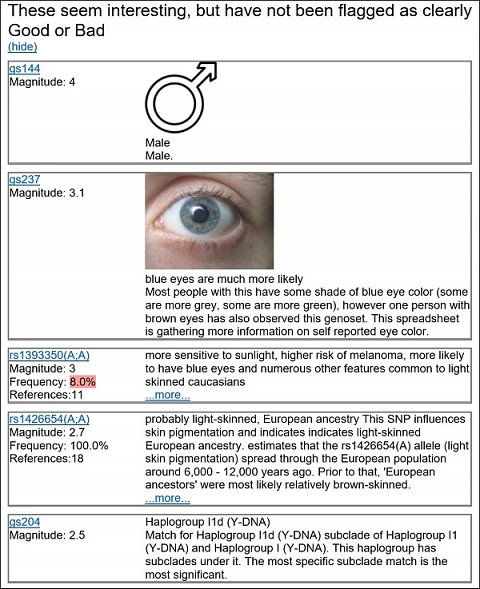

In the ‘Interesting overly simplified’ section, I saw dozens of neutral variants listed, the top five are shown below:

My top five Interesting genetic variants.

As you can see, each genetic variant is listed with a lot of technical information, and the summary doesn’t always fully interpret the result. That said, you can click-through to each variant’s SNPedia entry, and even better, you can click-through to the scientific paper(s) that associates the variant to a genetic predisposition.

There were lots of other sections in the Promethease report: A section showing the genetic variants linked to medicines, a section showing the variants linked to medical conditions, a miscellaneous section covering variants linked to ageing, weight management, breast size etc., and a section listing variants unique to me that don’t yet have an interpretation.

Summary

I’m glad I bought my 10x WGS from Full Genomes, and I’m glad I didn’t wait until the price of the 30x came down. Despite having to consider any result from the 10x WGS as a rough estimate, I was excited to discover what was possible today, and I was especially interested to read through the 60,000 known variants I carry!

It’s been a challenging experience trying to work out which WGS files are useful, how to open them, and what tools I should use to interpret them. If the Promethease tool hadn’t been available, I don’t think I’d be able to say I was happy with my purchase. Fortunately, the ability to analyse my WGS for only $10 more really made it worthwhile.

I would highly recommend that anyone who’s enthusiastic about exploring their DNA buy their WGS. Even though your WGS won’t come with a user-friendly analysis, if you’re prepared to see information that you don’t understand when using Promethease-style tools, the information you will understand is definitely worth it.

In terms of the mtDNA results that we produced, we offer an interpretation on request. A request was not made when this review was written and we'd like to provide the following information so the reviewer may receive the full benefit of our services.

We uploaded the FASTA.txt file containing the mtDNA data to http://dna.jameslick.com/mthap, which generated three maternal haplogroup matches:

1) I2a

Defining Markers for haplogroup I2a:

HVR2: 73G 152C 199C 204C 207A 250C 263G 573.1C

CR: 750G 1438G 1719A 2706G 4529T 4769G 7028T 8251A 8860G 10034C 10238C 10398G 11065G 11719A 12501A 12705T 13780G 14766T 15043A 15326G 15758G 15924G

HVR1: 16129A 16145A 16223T 16391A

2) I2a2

Defining Markers for haplogroup I2a2:

HVR2: 73G 152C 199C 204C 207A 250C 263G 573.1C

CR: 750G 1438G 1719A 2706G 4529T 4769G 7028T 8251A 8860G 9266A 10034C 10238C 10398G 11065G 11719A 12501A 12705T 13780G 14766T 15043A 15326G 15758G 15924G

HVR1: 16129A 16145A 16223T 16391A

3) I2

Defining Markers for haplogroup I2:

HVR2: 73G 152C 199C 204C 207A 250C 263G 573.1C

CR: 750G 1438G 1719A 2706G 4529T 4769G 7028T 8251A 8860G 10034C 10238C 10398G 11719A 12501A 12705T 13780G 14766T 15043A 15326G 15758G 15924G

HVR1: 16129A 16223T 16391A

We saw that 100% of the mtDNA was sequenced and that I2a is the closest maternal haplogroup. Close matches can be found in the public projects, a good starting point is https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_I_%28mtDNA%29, and we recommend that the FASTA.txt file is also uploaded to GenBank to help further genetic research. An explanation of this process can be found here: http://www.ianlogan.co.uk/submission.htm

Visit Full Genomes to learn more about this DNA testing service >