-

Genomepatri

review on 8 June 2018

by Rebecca Fishwick

At a Glance

Summary

I found Genomepatri by Mapmygenome to be very comprehensive. The test covered many areas of genetic health, particularly predispositions to certain diseases. Their genetic counselling service was included as part of the test, and helped to demystify the results so they were easier to understand. Their follow-up report offered useful recommendations that I felt I could incorporate into my routine without them being overwhelming. Their customer service was responsive and friendly, and altogether I felt supported during the entire process.

Full Review

Mapmygenome is a molecular diagnostics company founded in 2013 by CEO Anu Acharya, and is based in Hyderabad, India. Acharya was previously the founding CEO of Ocimum Biosolutions, a biosciences informatics company. In 2016, Mapmygenome was nominated as one of seven finalists for the Wall Street Journal’s Annual Startup Showcase.

Their services combine genetic health analysis with self-reported health history to inform people of their potential risks, and make them more proactive about their health.

Product Expectations

At first glance, it was clear there was a lot of depth to the Mapmygenome website. The three main tests they advertised were Genomepatri, MyFitGene and MedicaMap. Genomepatri was a comprehensive genomic health analysis test, while MyFitGene appeared to be a more focussed fitness DNA test, and MedicaMap was a medical drug response test.

I wanted to know more about the test I would take, and so I headed to the information page for Genomepatri.

They called Genomepatri the “next generation health test”. It would assess my “inherited and acquired” health risks for more than 100 health conditions, and provide insights into my predispositions to various conditions, traits, lifestyle tendencies, drugs/medications, and more.

There was a “How it works” section, which went through the steps of collecting a sample, the laboratory process, creating my report, genetic counselling, and the post-counselling feedback report.

I found a list of the genetic traits and predispositions covered by Genomepatri. There were quite a few! The areas covered included: cancer predisposition, cardio health, skin and hair, diabetes, women’s health, lifestyle, eye health, men’s health, bones and joints, immune diseases, gastro health, drug response, and kidney, lung and brain health.

I decided to have a look through the FAQs section. Here, I learned that Mapmygenome used the services of Ocimum Biosolutions, which has an ISO certified lab.

My data would be analysed on an Illumina chip, and I could request a copy of my raw data. They used genetic markers suitable for the Indian population, screening for predispositions to diseases prevalent in India, and using data from Ocimum Biosolutions accumulated for over 14 years.

Ordering Experience

Adding Genomepatri to my basket, I found I could ship within India, or internationally.

To purchase the test, I had to create an account. This required my name, email address, date of birth, gender, mobile number, and a password.

I wasn’t asked to agree with the Terms and Conditions, so I went in search of these myself.

Here, I read that the genetic risk profile is “not diagnostic in nature”, and shouldn’t be used as such. Having “high risk” for certain conditions did not necessarily mean that I would develop them.

There was a charge for international shipping and handling. I would be responsible for returning the sample to Mapmygenome, and for any charges involved. (Shipments within India were handled through a courier service.)

To protect my privacy, my DNA sample would be assigned a unique ID in place of my name before entering the lab. If I consented, my anonymised information would be used for research. Mapmygenome wouldn’t share my information with unaffiliated parties, except to allow me to “use the product as desired”, or if required to do so by law. If the organisation was sold, my information could be one of the transferred assets.

It was possible to request a refund, though only requests submitted within 24 hours of purchase would be processed.

In the Privacy Policy, I read that I may be contacted for marketing purposes, though I could opt out. They listed the cookies they used, and what they were for. Again, I was told my information would be kept confidential.

Having looked through their policies, I was happy to continue with my order.

The kit arrived in a compact box as depicted on the website. The buccal swab came with instructions for taking a sample, and the process was quick and straightforward. There was a booklet containing the ‘Test Requisition Form’, ‘Consent’ form, and ‘Health History Questionnaire’.

I had to sign my agreement to the Terms and Conditions, and give my “informed consent” for genetic testing, providing my name and contact details. I could also consent to having my anonymised data used for research.

The Health History Questionnaire was pretty extensive, and covered more areas of personal health than I would ever have thought of. Some mental health questions were included, which I thought some people may not be comfortable answering (though these could be left blank).

There was some confusing (possibly outdated?) information with the kit, telling me to register it online before returning it. Yet when I logged into my account, I could find no way of registering. I contacted customer services, and received a prompt response, saying they would register the kit for me once they received it.

After sealing and addressing the box, I sent it back to the address provided.

17 days after sending the sample back, I received an email saying that it had been received. There was a link to a digital consent form, which I filled in, although I’d already signed a paper form.

About a month after returning my sample, I received an email saying my results were ready.

The Results

My results email included a link to access my report. This link would expire after 30 days, after which I could request a copy of the PDF. Clicking the link started an automatic download (I had to enable pop-ups for it to work).

I emailed customer service for a copy of my raw data, which was sent to me that same day.

Results Section: Introduction

My report began with an introduction about the company, and a section about “Understanding Your Results”.

This explained what was meant by “relative risk”. This was the probability I had of developing a condition, and depended on the SNP(s) I had, which could make my risk higher, lower, or neutral.

There was an explanation of what “SNPs” (or Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) were: variations in my genetic code where a single nucleotide (or letter) is different. These genetic variants affect traits like susceptibility or resistance to disease, how I respond to drugs or chemicals, and so on.

There was a disclaimer, saying that the report was based solely on my genetics and not my medical history, and a genetic predisposition did not count as a diagnosis.

Results Section: Overview

There was a “Snapshot” of my genetic profile, with basic information about my traits and my risk of developing certain conditions. Those I had a higher-than-average risk of developing had a red flag beside them (shown below).

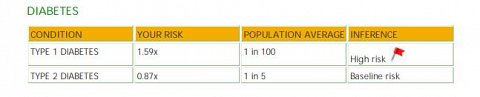

My relative risks for developing diabetes, types 1 and 2.

As you can see, I was shown as having a high risk for developing type 1 diabetes. Since the population average was shown as 1 in 100, and my risk was 1.59 times that, my actual genetic risk was still only 159 in 10,000, or 1.6%.

I questioned whether this level of risk was really worth flagging as “high”, and I was interested to read more about the SNPs that had contributed to this score.

For most conditions, I had only a baseline (low) or medium risk of developing them. But for a few conditions I had a higher risk of development. These included coronary heart disease, stroke and melanoma (a form of skin cancer).

Results Section: My Genetic Traits

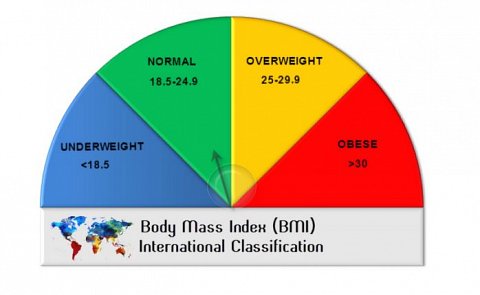

A chart showed where my predicted Body Mass Index (BMI) fell from a prediction based on my genes (shown below).

My predicted BMI according to my genetics.

The chart pictured above shows my estimated BMI according to the international classification; another showed my BMI according to Asian Indian classification. For both charts, I fell within the “Normal” range.

I learned that hereditary factors accounted for “nearly 60%” of variability for obesity around the world, and genome-wide studies had discovered over 25 genetic variants related to obesity.

I was surprised to discover that I had a slightly high risk for obesity. They had listed four associated SNPs, though I wasn’t sure which of these were actually putting me at risk. I’ve always had a fast metabolism, which I’d supposed was genetic – but apparently not.

The complications and risk factors associated with obesity were listed. People with a BMI above 30 were more at risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, gallstones, stroke, certain cancers, and so on.

The risk factors for obesity included genetics, family lifestyle, diet and lifestyle, certain medications, and certain medical conditions.

Next, I had a look at my predicted cholesterol levels. I found I had a slightly increased risk of high LDL cholesterol level: the “bad” type. On the other hand, I also had a slightly increased likelihood of a high level of HDL cholesterol: the “good” kind. I read that a higher level of LDL cholesterol could cause damage to arteries, and was linked to cardiovascular disease.

I also had a slightly high risk of developing “hypertriglyceridemia”, which involves overly high levels of triglycerides (fat molecules) in the bloodstream.

Where diet and exercise were concerned, I had an average response to dietary fats, and so a “normal” diet was recommended. My likelihood for resisting weight loss and regaining weight was slightly higher than average, which surprised me.

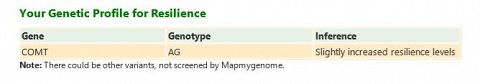

One trait that struck me as a little vague was “resilience”. This looked at the COMT gene, for which I had the genotype AG (shown below).

The gene associated with “resilience”, and my genotype.

My genotype was associated with slightly increased resilience levels. I read that people with greater resilience were better at overcoming tough situations and trauma. Variations in the COMT gene could affect anxiety levels, pain threshold, empathy, and vulnerability.

Moving on, I found I had low risks for hypertension (high blood pressure), alcoholism, alcohol flush reaction, nicotine dependence, and osteoporosis (which causes weak bones).

They had also listed predispositions to vitamin deficiencies. I found I was predisposed to slightly reduced levels of vitamins B6 and D, but had regular levels of vitamin B9 (folate) and vitamin C.

There were a couple more personality-related traits. I found that my GG genotype of the DRD2 gene meant that I was better disposed to feedback-based learning, which made me less likely to repeat errors. It also meant that I was less likely to have addictive behaviour. Additionally, my version of the BDNF gene – for which my genotype was AG – predisposed me to a slightly reduced memory, and an increased risk for anxiety disorder.

Results Section: My Predispositions

There was more about my predisposition to type 1 diabetes in the diseases section.

Though I had several genetic variants associated with type 1 diabetes, my actual genetic risk of developing it was only 1.59 times the average. While this might sound alarming, the population average was only 1 in 100, and so my genetic risk was really only 1.59%.

Since type 1 diabetes is generally diagnosed in childhood, I wasn’t concerned about developing it.

I found I had four of the five genetic variants associated with coronary heart disease. Still, my personal risk seemed almost negligible, being approximately 1.22%.

I had similar stories for stroke, hypothyroidism, and melanoma: though my genetic risk was higher than average, my overall risk was not significantly increased. But I supposed that had I waited to ask my genetic counsellor, she could have told me the same thing.

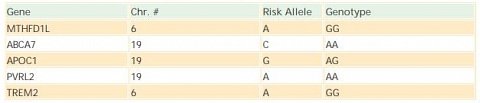

I also had a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. My relative risk was 2.46 times the population average, which was 62 in 1000. This gave me a 15% chance of developing Alzheimer’s. As with the other diseases listed, there was a chart breaking down the genes they had looked at, the associated alleles, and the genotype (allele pair) I had (shown below).

A chart showing the genes associated with Alzheimer’s, the risk alleles, and my genotype.

Considering I had only two of the five associated variants, a 15% risk seemed pretty high.

Still, I read that the genetic basis for late-onset Alzheimer’s was “not well known”, and there were other contributing factors. Poor cardiovascular health was one of these, as were head trauma, exposure to environmental toxins, and certain viral infections.

Risk of developing Alzheimer’s could be reduced by taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and engaging in intellectual activities such as reading, crossword puzzles, and social interaction.

Finally, I found I had higher-than-average genetic risks of developing Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and lupus. My actual likelihood of developing MS was 0.016%, while my likelihood of developing lupus was only 0.2%.

Results Section: Skin and Hair

The “Skin” section began with an assessment of my ability to detox. They looked at the SOD2 gene, one of the genes responsible for detoxification. My AG genotype meant that I had slightly reduced antioxidant levels, which could lead to dry or rough skin, wrinkles and fine lines, cellular deterioration, premature ageing, and a possible increased risk of cancer.

Risk factors were: excessive exposure to UV rays, lack of skincare routine, poor hydration, and a lack of antioxidants in my diet. Elevated stress levels and a hectic lifestyle could also increase cellular degeneration.

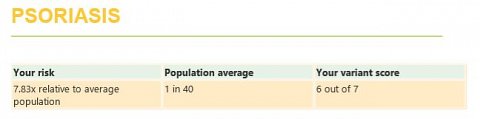

My risk for psoriasis was higher than I would have liked (shown below).

My relative risk of developing psoriasis.

As you can see, I had six of the seven variants associated with psoriasis, which made my relative risk 7.83 times the population average of 1 in 40. This gave me nearly a 20% risk of developing psoriasis.

I wasn’t surprised by this result, since my mother has psoriasis, and I knew that it was partly hereditary. In the information provided, I saw that someone who has a parent with psoriasis has a 16% chance of inheriting the disease.

Reading on, I found the non-genetic risk factors associated with the disease included smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption, infectious diseases, certain medications, and stress.

For vitiligo I also had an increased risk, but really this was close to nothing, being only 0.66% – basically no risk at all.

Results Section: Inherited Conditions and Drug Responses

For the “Inherited Conditions” section, I tested positive for neither of the conditions listed, and didn’t carry any of the related genes. There was plenty of information provided for both G6PD deficiency and Phenylketonuria (PKU).

In the “Drug Responses” section, I found I had either a normal or high rate of metabolism for each drug, and a low risk of drug-induced toxicity or sensitivity. The only exception was flurbiprofen, a type of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), for which I had a slightly high risk of drug sensitivity. Information was provided for each drug, including possible adverse effects.

The report ended with a summary of the conditions covered.

Results Section: My Consultation

I could book my counselling session through the website, which was pretty simple. I could select a time (time zone was automatically detected), and my preferred counsellor (though I might get another). I received a confirmation email, with a link to fill in a digital version of the Health History Questionnaire.

My consultation lasted for about an hour. My counsellor took me through the different areas of my report, and discussed the items that had been flagged for higher risk.

Many of my genetic risks weren’t actually very high. For many of them, my counsellor reassured me that I didn’t need to be too worried, while also giving me recommendations for how I could reduce my risks.

As I have risks for melanoma, psoriasis and vitiligo, she recommended I use a sunblock with 30+ SPF. Since I have genetically low vitamin D levels, she didn’t want me to avoid the sun entirely. She also recommended a diet high in antioxidants, such as green tea and tomatoes, and foods high in omega fats, such as olive oil.

We discussed my own and my family’s health history, and what these might mean for me and my genetic risk scores. My counsellor was very friendly and informed, and willing and able to answer the questions I had.

Results Section: My Follow-up Report

About a week after my consultation, I received my Post-Genetic Counselling Recommendations. This took into account both my family’s medical history, and my self-reported health history.

There was a table showing my genetic risks that had been classed as “high” or “medium”. One column showed whether these conditions were currently diagnosed, while another had my genetic counsellor’s assessment of my actual risk.

All of my high risks had been reduced to medium, while my medium risk of obesity had been reduced to “normal” (which I took to mean baseline risk).

There were also recommendations of what I could do to reduce my risks, such as wearing sunblock to diminish my risks of melanoma, vitiligo, and psoriasis.

There were some diet and lifestyle recommendations. These included suggestions like using safflower oil for cooking, which is high in healthy fats. I should take supplements only if blood tests reveal a lack of certain nutrients, and otherwise consume foods rich in antioxidants (such as tomatoes and berries), try to decrease my salt intake, and avoid processed foods.

There were also screening tests recommended for me, including a lipid profile (to be taken every six months) and a thyroid function test.

Summary

I found Genomepatri by Mapmygenome to be very comprehensive. The test covered many areas of genetic health, particularly predispositions to certain diseases. Their genetic counselling service was included as part of the test, and helped to demystify the results so they were easier to understand. Their follow-up report offered useful recommendations that I felt I could incorporate into my routine without them being overwhelming. Their customer service was responsive and friendly, and altogether I felt supported during the entire process.