-

How Happy Are You

review on 16 April 2018

by Rebecca Fishwick

At a Glance

Summary

The ‘How Happy Are You?’ web app by USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center gave me a fun and interesting way to reuse my genetic information. Currently, the accuracy of their predictions isn’t very high, though they hope to improve it with research as people contribute their DNA and survey answers.

In order to access the web app, it was necessary to create an account with the DNA marketplace Gencove. They allowed me to upload my data from a range of sources, and also gave the option to purchase one of their DNA testing kits, for a competitively low price.

Full Review

The University of Southern California Behavioral and Health Genomics Center brings together leading researchers in the emerging field of social-science genomics, studying how genetic variation relates to behavioural phenotypes, such as educational attainment, subjective well-being, and economic preferences.

In order to access the ‘How Happy Are You?’ web app by the USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center, I had to sign up to a marketplace called Gencove.

Gencove was founded in 2017 by three scientists at the New York Genome Center: Joe Pickrell, Kaja Wasik and Tomaz Berisa. The company aims to make genome sequencing accessible and interpretable. They plan to do this by building inexpensive and enjoyable genomic applications, using the data generated to find the genetic variants that really matter, and build the next generation of genetic tests based on these findings, while continuously growing their knowledge and improving.

Product Expectations

I could download the Gencove marketplace app on my phone, or log into it via an internet browser. I chose the latter option. The Gencove site was bright, dynamic, and interesting. There was a demo of the interactive map included in their ‘Explore Your Ancestry’ web app, showing which regions they covered (which was most of the globe!).

Scrolling down the page, I was given a preview of which web apps and research projects I would be able to access after signing up. Most of these were developed by Gencove, but the ‘How Happy Are You?’ web app (for exploring the genetics of happiness) was developed by the USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center.

The ‘How does it work?’ section gave me a breakdown of the three stages of using Gencove: inputting DNA data (either by uploading my genetic information, or ordering a kit), connecting with the free Gencove web apps or external web apps and research projects, tracking my activity and securely storing my DNA files.

At the bottom of the page, I found an FAQs section. Here, I discovered that a DNA upload would typically be processed within around 30 minutes, while results from a DNA collection kit would take six to ten weeks from when the sample was returned to Gencove. They described the type of sequencing they used as “genotype imputation” which “fills in” blanks where genetic variants hadn’t “been directly measured”. I’d never heard of this and it sounded a bit like they would guess some of my data, but a quick scan of the linked Wikipedia article reassured me that this was a legitimate method.

There was also a link to the Privacy Policy, in which I found out that Gencove would collect and store my name, email address and password, my responses to questions and quizzes about my personal preferences and habits, my genomic information, and any other personal information I might provide. If I chose to participate in their research study, then this data could be used for research. I was pleased to read that they wouldn’t pass on my information to third parties, except to provide me with the service and to comply with the law.

Ordering Experience

As previously mentioned, the site gave me a choice of uploading my genetic data for free from another source or purchasing a DNA testing kit from them, which was very inexpensive compared to other providers (though not available in the UK). Since I had already had my DNA analysed by 23andMe, I chose to upload this data, but was informed that Gencove accepted data “from all major genomics providers”.

Before uploading, I had to sign up to a Gencove account. I had only to enter my email, name (which didn’t have to be a full name) and a password, before submitting. There was some text saying that by creating an account I was agreeing to the Terms and the Privacy Policy. However, I wasn’t required to read these before clicking to sign up.

Once I had created my free account, I saw I had access to eleven different web apps, including a ‘Relative Radar’ for finding genetic relatives, ‘My Genome’ for exploring my genomic data, and an ‘Open Humans’ web app where I could contribute my genetic data to research and citizen science. I was most interested in the ‘How Happy Are You?’ web app, which would predict my predisposition to happiness based on my genetics.

After creating my account, I was sent an email asking me to verify it, which I did before uploading my data.

Data Upload

Clicking on ‘Upload Data’, I was taken to a page about Gencove research. This was optional, and I could skip to the bottom if I wasn’t interested in taking part.

Looking through the ‘Gencove Consent Document’, I found that the study was run by Gencove, Inc., and aimed to identify genetic variants that may influence personal characteristics and disease risk. In order to participate in the study, I would have to use and return one of Gencove’s saliva collection kits. I participated in the study, then my genomic data would be stored indefinitely, as it would be used for any new studies that may arise. However, I would be able to withdraw at any time. I also read that any genetic data would be identified by a barcode (rather than by name), and any personal identifiers or contact information would not be shared with third parties, except if required by law. Anyone consenting to the study would have to be older than 18.

The next page allowed me to upload my genetic data directly from my computer. There was a ‘Need help?’ section below, with screenshots showing me how I could download my information from several different providers.

I uploaded the .zip file of my genetic information from 23andMe, which took about fifteen minutes to process. I clicked a button to go back to the homepage, where I could view a progress bar of how long the upload was taking.

The Results

I was sent an email once my data had finished processing and was immediately able to access the web apps offered by Gencove and their associates, including ‘How Happy Are You?’ by USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center.

Results Section: Preliminaries to Happiness

Clicking on ‘How Happy Are You?’ took me to a page saying I was authorising USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center to access the genetic data stored in my Gencove account. There was also a message from Gencove telling me that they had filled in gaps in my genome using “imputation”, with a link to find out more. It was made clear that the data in my Gencove account could not be used for medical purposes, as it may not be entirely accurate. Soon after clicking “Continue”, an email from Gencove popped up, telling me I had successfully joined ‘How Happy are You?’ – a useful security feature.

The Steps to Happiness.

The next page broke down the steps of finding out just how genetically happy I am. It wanted me to answer a few questions for research purposes, after which I could see how my answers compared to the general population (which I thought would be quite interesting!), and lastly I would learn what my genetics predicted about my happiness.

I was then taken to a Consent form (the hidden 0.5th step!). As with Gencove, I did not have to consent to participate in their studies, but I would have to agree to their Terms in order to continue. The purpose of this study was to help the USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center learn about genetic influences on behavioural traits, such as subjective well-being, and to learn through user responses how people respond to their genetic information. There was a promise that my information would be confidential, and that I could opt out of the study at any time.

Results Section: Survey

Next, I answered a series of thirteen questions about my personal happiness, and a few general ones about myself (age, marital status, etc.). There was no information that I felt uncomfortable about providing. The only question with a ’Prefer not to answer’ category was about sex; this term was used rather than “gender”. Some questions had an ‘Other’ box, which required you to manually fill in an answer.

The last question asked me to predict where I thought I’d score in terms of happiness according to my genetics: lowest third (least disposed to be happy), middle third, or highest third (most disposed to be happy). I read that this prediction is currently not very accurate, though I expect they plan to improve this through research. I cautiously selected ‘middle third’.

Results Section: My Genetic Happiness Score

After submitting my answers, I was taken to my results. First, there was an explanation of ‘subjective well-being’. I read that many different factors could influence a person’s subjective well-being, including the quality of their relationships, their work life, how much they exercise, how much they sleep, and other contributing factors. In addition to this, scientists believe that genes can explain up to 40% of the differences in subjective well-being between individuals (there was a link to an article about this, and so it did not seem like an arbitrary claim).

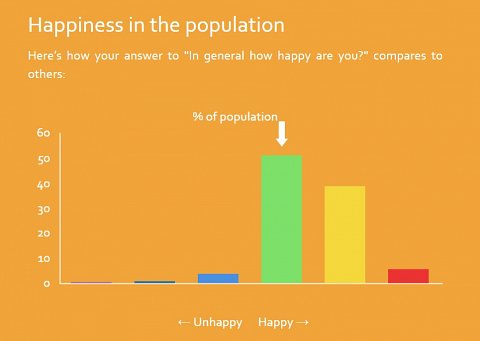

According to the answers I gave, I was ‘moderately happy’, falling into the same range as about 50% of the population, according to their graph (shown below).

A graph showing ‘Happiness in the Population’.

At first, this graph was not very easy to read, as it appeared that the population percentage at the far right of the graph were very unhappy, when really this showed a smaller percentage of people scoring as “very happy”.

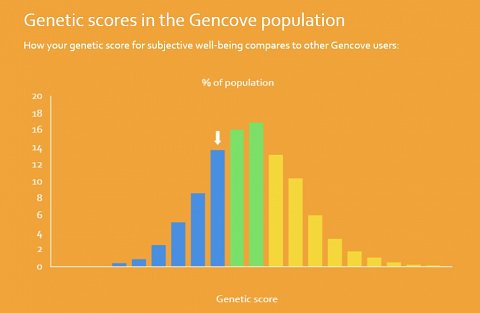

Interestingly, according to my genetic score, I fell into the lowest third for happiness, with low confidence.

My genetic happiness score.

I found this rather surprising, though of course – as had already been stated – environmental and lifestyle factors also play significant roles in overall happiness. Looking at another graph, I saw that while I had been placed in the lowest third, I was in its upper echelons (shown below).

A graph showing my genetic happiness score compared to the general population.

Reading on, I found that this genetic score only accounted for 1% of the differences in subjective well-being among people of European ancestry, and so currently, in their own words, it was “not very accurate at all”. Also, this score was even less accurate among people of non-European ancestry, since most genetic databases available to researchers currently come from Europe or the US. Still, I understood that this was a budding area of research, and so I was pleased to have contributed to this study.

I was given the option of answering a few more questions, which I chose to do. These turned out to be questions about how much I’d enjoyed learning about my genetic score, a sneakier question testing how closely I’d read my results page, and a question about my household income. If I wanted to, there was a link allowing me to tweet or share my results on Facebook.

Summary

The ‘How Happy Are You?’ web app by USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center gave me a fun and interesting way to reuse my genetic information. Currently, the accuracy of their predictions isn’t very high, though they hope to improve it with research as people contribute their DNA and survey answers.

In order to access the web app, it was necessary to create an account with the DNA marketplace Gencove. They allowed me to upload my data from a range of sources, and also gave the option to purchase one of their DNA testing kits, for a competitively low price.

See a description of this DNA test from USC Behavioral and Health Genomics Center >